Jamaican Marriage License Records

Jamaica provides wedding planning and marriage services to couples from around the world. Marriage records are maintained by the Registrar General's Department. Requests are made online and payments must be made before the record request will be processed.

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Usain St Leo Bolt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname(s) | Lightning Bolt[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Jamaican | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 21 August 1986 (age 32) Sherwood Content, Jamaica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residence | Kingston, Jamaica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.95 m (6 ft 5 in)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 94 kg (207 lb)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sport | Track and field | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Event(s) | Sprints | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Club | Racers Track Club | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coached by | Glen Mills[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Retired | 2017[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Achievements and titles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal best(s) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Usain St Leo Bolt (/ˈjuːseɪn/[12]; born 21 August 1986) is a Jamaican retired sprinter. He is a world record holder in the 100 metres, 200 metres and 4 × 100 metres relay. His reign as Olympic Games champion in all of these events spans three Olympics. Owing to his achievements and dominance in sprint competition, he is widely considered to be the greatest sprinter of all time.[13][14][15][16]

A nine-time Olympic gold medalist, Bolt won the 100 m, 200 m and 4 × 100 m relay at three consecutive Olympic Games, although he lost the 2008 relay gold medal about nine years afterward due to a teammate's long-delayed doping disqualification. He gained worldwide fame for his double sprint victory in world record times at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, which made him the first person to hold both records since fully automatic time became mandatory. Bolt is the only sprinter to win Olympic 100 m and 200 m titles at three consecutive Olympics (2008, 2012 and 2016).

An eleven-time World Champion, he won consecutive World Championship 100 m, 200 m and 4 × 100 metres relay gold medals from 2009 to 2015, with the exception of a 100 m false start in 2011. He is the most successful athlete of the World Championships, was the first athlete to win four World Championship titles in the 200 m and is the joint-most successful in the 100 m with three titles.

Bolt improved upon his second 100 m world record of 9.69 with 9.58 seconds in 2009 – the biggest improvement since the start of electronic timing. He has twice broken the 200 metres world record, setting 19.30 in 2008 and 19.19 in 2009. He has helped Jamaica to three 4 × 100 metres relay world records, with the current record being 36.84 seconds set in 2012. Bolt's most successful event is the 200 m, with three Olympic and four World titles. The 2008 Olympics was his international debut over 100 m; he had earlier won numerous 200 m medals (including 2007 World Championship silver) and holds the world under-20 and world under-18 records for the event.

His achievements as a sprinter have earned him the media nickname 'Lightning Bolt', and his awards include the IAAF World Athlete of the Year, Track & Field Athlete of the Year, BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year (three times) and Laureus World Sportsman of the Year (four times). Bolt retired after the 2017 World Championships, when he finished third in his last solo 100 m race, opted out of the 200 m, and pulled up in the 4×100 m relay final.

Stating that it was his 'dream' to play professional association football, in August 2018 Bolt began training with Australian A-League club the Central Coast Mariners as a left-winger. On 12 October 2018, Bolt scored twice for the team in a friendly match. He left the club the following month, and in January 2019 announced that he would not be pursuing a career in football. In 2018, Bolt co-founded and launched Bolt Mobility in the U.S., an e-scooter which can reach speeds of up to 15mph. In May 2019, the company expanded its services to Europe, introducing the product first in Paris. [17]

- 1Early years

- 2Professional athletics career

- 4Personal life

- 8Statistics

- 12External links

Early years

Bolt was born on 21 August 1986 to parents Wellesley and Jennifer Bolt[10] in Sherwood Content,[18] a small town in Jamaica. He has a brother, Sadiki,[19] and a sister, Sherine.[20][21] His parents ran the local grocery store in the rural area, and Bolt spent his time playing cricket and football in the street with his brother,[22] later saying, 'When I was young, I didn't really think about anything other than sports.'[23] As a child, Bolt attended Waldensia Primary, where he began showing his sprint potential when he ran in his parish's annual national primary school meet.[1] By the age of twelve, Bolt had become the school's fastest runner over the 100 metres distance.[24]

Upon his entry to William Knibb Memorial High School, Bolt continued to focus on other sports, but his cricket coach noticed Bolt's speed on the pitch and urged him to try track and field events.[25]Pablo McNeil, a former Olympic sprint athlete,[26] and Dwayne Jarrett coached Bolt,[27] encouraging him to focus his energy on improving his athletic abilities. The school had a history of success in athletics with past students, including sprinter Michael Green.[1] Bolt won his first annual high school championships medal in 2001; he took the silver medal in the 200 metres with a time of 22.04 seconds.[1] McNeil soon became his primary coach, and the two enjoyed a positive partnership, although McNeil was occasionally frustrated by Bolt's lack of dedication to his training and his penchant for practical jokes.[26]

When Bolt was a boy, he attended Sherwood Content Seventh-day Adventist Church in Trelawny, Jamaica, with his mother. His mother didn't serve pork to him in accordance with Adventist beliefs.[28]

Early competitions

Performing for Jamaica in his first Caribbean regional event, Bolt clocked a personal best time of 48.28 s in the 400 metres in the 2001 CARIFTA Games, winning a silver medal. The 200 m also yielded a silver, as Bolt finished in 21.81 s.[29]

He made his first appearance on the world stage at the 2001 IAAF World Youth Championships in Debrecen, Hungary. Running in the 200 m event, he failed to qualify for the finals, but he still set a new personal best of 21.73 s.[30] Bolt still did not take athletics or himself too seriously, however, and he took his mischievousness to new heights by hiding in the back of a van when he was supposed to be preparing for the 200 m finals at the CARIFTA Trials. He was detained by the police for his practical joke, and there was an outcry from the local community, which blamed coach McNeil for the incident.[26] However, the controversy subsided, and both McNeil and Bolt went to the CARIFTA Games, where Bolt set championship records in the 200 m and 400 m with times of 21.12 s and 47.33 s, respectively.[29] He continued to set records with 20.61 s and 47.12 s finishes at the Central American and Caribbean Junior Championships.[31]

Bolt is one of only nine athletes (along with Valerie Adams, Veronica Campbell-Brown, Jacques Freitag, Yelena Isinbayeva, Jana Pittman, Dani Samuels, David Storl, and Kirani James) to win world championships at the youth, junior, and senior level of an athletic event. Former Prime Minister P. J. Patterson recognised Bolt's talent and arranged for him to move to Kingston, along with Jermaine Gonzales, so he could train with the Jamaica Amateur Athletic Association (JAAA) at the University of Technology, Jamaica.[26]

Rise to prominence

The 2002 World Junior Championships were held in front of a home crowd in Kingston, Jamaica, and Bolt was given a chance to prove his credentials on a world stage. By the age of 15, he had grown to 1.96 metres (6 ft 5 in) tall, and he physically stood out among his peers.[1] He won the 200 m in a time of 20.61 s,[32] which was 0.03 s slower than his personal best of 20.58 s, which he set in the 1st round.[33] Bolt's 200 m win made him the youngest world-junior gold medallist ever.[34] The expectation from the home crowd had made him so nervous that he had put his shoes on the wrong feet. However, it turned out to be a revelatory experience for Bolt, as he vowed never again to let himself be affected by pre-race nerves.[35] As a member of the Jamaican sprint relay team, he also took two silver medals and set national junior records in the 4×100 metres and 4×400 metres relay, running times of 39.15 s and 3:04.06 minutes respectively.[36][37]

The rush of medals continued as he won four golds at the 2003 CARIFTA Games and was awarded the Austin Sealy Trophy for the most outstanding athlete of the games.[38][39][40] He won another gold at the 2003 World Youth Championships. He set a new championship record in the 200 m with a time of 20.40 s, despite a 1.1 m/shead wind.[41]Michael Johnson, the 200 m world-record holder, took note of Bolt's potential but worried that the young sprinter might be over-pressured, stating, 'It's all about what he does three, four, five years down the line'.[42] Bolt had also impressed the athletics hierarchy, and he received the IAAF Rising Star Award for 2002.[43]

Bolt competed in his final Jamaican High School Championships in 2003. He broke the 200 m and 400 m records with times of 20.25 s and 45.35 s, respectively. Bolt's runs were a significant improvement upon the previous records, beating the 200 m best by more than half a second and the 400 m record by almost a second.[1] While Bolt improved upon the 200 m time three months later, setting the still-standing World youth best at the 2003 Pan American Junior Championships.[44] The 400 m time remains No. 6 on the all-time youth list, surpassed only once since, by future Olympic champion Kirani James.[45]

Bolt turned his main focus to the 200 m and equalled Roy Martin's world junior record of 20.13 s at the Pan-American Junior Championships.[1][46] This performance attracted interest from the press, and his times in the 200 m and 400 m led to him being touted as a possible successor to Johnson. Indeed, at sixteen years old, Bolt had reached times that Johnson did not register until he was twenty, and Bolt's 200 m time was superior to Maurice Greene's season's best that year.[42]

Bolt was growing more popular in his homeland. Howard Hamilton, who was given the task of Public Defender by the government, urged the JAAA to nurture him and prevent burnout, calling Bolt 'the most phenomenal sprinter ever produced by this island'.[42] His popularity and the attractions of the capital city were beginning to be a burden to the young sprinter. Bolt was increasingly unfocused on his athletic career and preferred to eat fast food, play basketball, and party in Kingston's club scene. In the absence of a disciplined lifestyle, he became ever-more reliant on his natural ability to beat his competitors on the track.[47]

As the reigning 200 m champion at both the World Youth and World Junior championships, Bolt hoped to take a clean sweep of the world 200 m championships in the Senior World Championships in Paris.[1] He beat all comers at the 200 m in the World Championship trials. Bolt was pragmatic about his chances and noted that, even if he did not make the final, he would consider setting a personal best a success.[42][48] However, he suffered a bout of conjunctivitis before the event, and it ruined his training schedule.[1] Realising that he would not be in peak condition, the JAAA refused to let him participate in the finals, on the grounds that he was too young and inexperienced. Bolt was dismayed at missing out on the opportunity, but focused on getting himself in shape to gain a place on the Jamaican Olympic team instead.[48] Even though he missed the World Championships, Bolt was awarded the IAAF Rising Star Award for the 2003 season on the strength of his junior record-equalling run.[43][49]

Professional athletics career

2004–2007 Early career

Under the guidance of new coach Fitz Coleman, Bolt turned professional in 2004, beginning with the CARIFTA Games in Bermuda.[1] He became the first junior sprinter to run the 200 m in under twenty seconds, taking the world junior record outright with a time of 19.93 s.[1][34] For the second time in the role, he was awarded the Austin Sealy Trophy for themost outstanding athlete of the 2004 CARIFTA Games.[38][39][50] A hamstring injury in May ruined Bolt's chances of competing in the 2004 World Junior Championships, but he was still chosen for the Jamaican Olympic squad.[51] Bolt headed to the 2004 Athens Olympics with confidence and a new record on his side. However, he was hampered by a leg injury and was eliminated in the first round of the 200 metres with a disappointing time of 21.05 s.[10][52] American colleges offered Bolt track scholarships to train in the United States while continuing to represent Jamaica on the international stage, but the teenager from Trelawny refused them all, stating that he was content to stay in his homeland of Jamaica.[21] Bolt instead chose the surroundings of the University of Technology, Jamaica, as his professional training ground, staying with the university's track and weight room that had served him well in his amateur years.[53]

The year 2005 signalled a fresh start for Bolt in the form of a new coach, Glen Mills, and a new attitude toward athletics. Mills recognised Bolt's potential and aimed to cease what he considered an unprofessional approach to the sport.[52] Bolt began training with Mills in preparation for the upcoming athletics season, partnering with more seasoned sprinters such as Kim Collins and Dwain Chambers.[54] The year began well, and in July, he knocked more than a third of a second off the 200 m CAC Championship record with a run of 20.03 s,[55] then registered his 200 m season's best at London's Crystal Palace, running in 19.99 s.[10]

Misfortune awaited Bolt at the next major event, the 2005 World Championships in Helsinki. Bolt felt that both his work ethic and athleticism had much improved since the 2004 Olympics, and he saw the World Championships as a way to live up to expectations, stating, 'I really want to make up for what happened in Athens. Hopefully, everything will fall into place'.[56] Bolt qualified with runs under 21 s, but he suffered an injury in the final, finishing in last place with a time of 26.27 s.[52][57] Injuries were preventing him from completing a full professional athletics season, and the eighteen-year-old Bolt still had not proven his mettle in the major world-athletics competitions.[58] However, his appearance made him the youngest ever person to appear in a 200 m world final.[59] Bolt was involved in a car accident in November, and although he suffered only minor facial lacerations, his training schedule was further upset.[60][61] His manager, Norman Peart, made Bolt's training less intensive, and he had fully recuperated the following week.[60] Bolt had continued to improve his performances, and he reached the world top-5 rankings in 2005 and 2006.[1] Peart and Mills stated their intentions to push Bolt to do longer sprinting distances with the aim of making the 400 m event his primary event by 2007 or 2008. Bolt was less enthusiastic, and demanded that he feel comfortable in his sprinting.[60][62] He suffered another hamstring injury in March 2006, forcing him to withdraw from the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, and he did not return to track events until May.[63] After his recovery, Bolt was given new training exercises to improve flexibility, and the plans to move him up to the 400 m event were put on hold.[58]

The 200 m remained Bolt's primary event when he returned to competition; he bested Justin Gatlin's meet record in Ostrava, Czech Republic. Bolt had aspired to run under twenty seconds to claim a season's best but, despite the fact that bad weather had impaired his run, he was happy to end the meeting with just the victory.[64] However, a sub-20-second finish was soon his, as he set a new personal best of 19.88 s at the 2006 Athletissima Grand Prix in Lausanne, Switzerland, finishing behind Xavier Carter and Tyson Gay to earn a bronze medal.[65] Bolt had focused his athletics aims, stating that 2006 was a year to gain experience. Also, he was more keen on competing over longer distances, setting his sights on running regularly in both 200 m and 400 m events within the next two years.[64]

Bolt claimed his first major world medal two months later at the IAAF World Athletics Final in Stuttgart, Germany. He passed the finishing post with a time of 20.10 s, gaining a bronze medal in the process.[10] The IAAF World Cup in Athens, Greece, yielded Bolt's first senior international silver medal.[10]Wallace Spearmon from the United States won gold with a championship record time of 19.87 s, beating Bolt's respectable time of 19.96 s.[66] Further 200 m honours on both the regional and international stages awaited Bolt in 2007. He yearned to run in the 100 metres but Mills was skeptical, believing that Bolt was better suited for middle distances. The coach cited the runner's difficulty in smoothly starting out of the blocks and poor habits such as looking back at opponents in sprints. Mills told Bolt that he could run the shorter distance if he broke the 200 m national record.[52] In the Jamaican Championships, he ran 19.75 s in the 200 m, breaking the 36-year-old Jamaican record held by Don Quarrie by 0.11 s.[1][21]

Mills complied with Bolt's demand to run in the 100 m, and he was entered to run the event at the 23rd Vardinoyiannia meeting in Rethymno, Crete. In his debut tournament run, he set a personal best of 10.03 s, winning the gold medal and feeding his enthusiasm for the event.[21][67]

He built on this achievement at the 2007 World Championships in Osaka, Japan, winning a silver medal.[10] Bolt recorded 19.91 s with a headwind of 0.8 m/s. The race was won by Tyson Gay in 19.76 s, a new championship record.[68]

Bolt was a member of the silver medal relay team with Asafa Powell, Marvin Anderson, and Nesta Carter in the 4×100 metres relay. Jamaica set a national record of 37.89 s.[69] Bolt did not win any gold medals at the major tournaments in 2007, but Mills felt that Bolt's technique was much improved, pinpointing improvements in Bolt's balance at the turns over 200 m and an increase in his stride frequency, giving him more driving power on the track.[52]

World-record breaker

The silver medals from the 2007 Osaka World Championships boosted Bolt's desire to sprint, and he took a more serious, more mature stance towards his career.[25] Bolt continued to develop in the 100 m, and he decided to compete in the event at the Jamaica Invitational in Kingston. On 3 May 2008, Bolt ran a time of 9.76 s, with a 1.8 m/stail wind, improving his personal best from 10.03 s.[70] This was the second-fastest legal performance in the history of the event, second only to compatriot Asafa Powell's 9.74 s record set the previous year in Rieti, Italy.[71] Rival Tyson Gay lauded the performance, especially praising Bolt's form and technique.[72] Michael Johnson observed the race and said that he was shocked at how quickly Bolt had improved over the 100 m distance.[73] The Jamaican surprised even himself with the time, but coach Glen Mills remained confident that there was more to come.[72]

On 31 May 2008, Bolt set a new 100 m world record at the Reebok Grand Prix in the Icahn Stadium in New York City. He ran 9.72s with a tail wind of 1.7 m/s.[74] This race was Bolt's fifth senior 100 m.[75] Gay again finished second and said of Bolt: 'It looked like his knees were going past my face.'[21] Commentators noted that Bolt appeared to have gained a psychological advantage over fellow Olympic contender Gay.[52]

In June 2008, Bolt responded to claims that he was a lazy athlete, saying that the comments were unjustified, and he trained hard to achieve his potential. However, he surmised that such comments stemmed from his lack of enthusiasm for the 400 metres event; he chose not to make an effort to train for that particular distance.[76] Turning his efforts to the 200 m, Bolt proved that he could excel in two events—first setting the world-leading time in Ostrava, then breaking the national record for the second time with a 19.67 s finish in Athens, Greece.[77][78] Although Mills still preferred that Bolt focus on the longer distances, the acceptance of Bolt's demand to run in the 100 m worked for both sprinter and trainer. Bolt was more focused in practice, and a training schedule to boost his top speed and his stamina, in preparation for the Olympics, had improved both his 100 m and 200 m times.[21][79][80]

2008 Summer Olympics

Bolt announced that he would double-up with the 100 metres and 200 metres events at the Beijing Summer Olympics. As the new 100 m world-record holder, he was the favourite to win both races.[81][82]Michael Johnson, the 200 m and 400 m record holder, personally backed the sprinter, saying that he did not believe that a lack of experience would work against him.[83] Bolt qualified for the 100 m final with times of 9.92 s and 9.85 s in the quarter-finals and semi-finals, respectively.[84][85][86]

—Tom Hammond, NBC Sports, with the call for the men's 100 metres final at the 2008 Summer Olympics.

In the Olympic 100 m final, Bolt broke new ground, winning in 9.69 s (unofficially 9.683 s) with a reaction time of 0.165 s.[87] This was an improvement upon his own world record, and he was well ahead of second-place finisher Richard Thompson, who finished in 9.89 s.[88] Not only was the record set without a favourable wind (+0.0 m/s), but he also visibly slowed down to celebrate before he finished and his shoelace was untied.[89][90][91] Bolt's coach reported that, based upon the speed of Bolt's opening 60 m, he could have finished with a time of 9.52 s.[92] After scientific analysis of Bolt's run by the Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics at the University of Oslo, Hans Eriksen and his colleagues also predicted a sub 9.60 s time. Considering factors such as Bolt's position, acceleration and velocity in comparison with second-place-finisher Thompson, the team estimated that Bolt could have finished in 9.55±0.04 s had he not slowed to celebrate before the finishing line.[93][94]

Bolt stated that setting a world record was not a priority for him, and that his goal was just to win the gold medal, Jamaica's first of the 2008 Games.[95] Olympic medallist Kriss Akabusi construed Bolt's chest slapping before the finish line as showboating, noting that the actions cost Bolt an even faster record time.[96]IOC president Jacques Rogge also condemned the Jamaican's actions as disrespectful.[97][98] Bolt denied that this was the purpose of his celebration by saying, 'I wasn't bragging. When I saw I wasn't covered, I was just happy'.[99]Lamine Diack, president of the IAAF, supported Bolt and said that his celebration was appropriate given the circumstances of his victory. Jamaican government minister Edmund Bartlett also defended Bolt's actions, stating, 'We have to see it in the glory of their moment and give it to them. We have to allow the personality of youth to express itself'.[100]

Bolt then focused on attaining a gold medal in the 200 m event, aiming to emulate Carl Lewis' double win in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.[101] Michael Johnson felt that Bolt would easily win gold but believed that his own world record of 19.32 s set at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta would remain intact at the Olympics.[102] Bolt eased through the first and second rounds of the 200 m, jogging towards the end of his run both times.[103] He won his semi-final and progressed to the final as the favourite to win.[104] Retired Jamaican sprinter Don Quarrie praised Bolt, saying he was confident that Johnson's record could be beaten.[43] The following day, at the final, he won Jamaica's fourth gold of the Games, setting a new world and Olympic record of 19.30 s.[105] Johnson's record fell despite the fact that Bolt was impeded by a 0.9 m/s headwind. The feat made him the first sprinter since Quarrie to hold both 100 m and 200 m world records simultaneously and the first to hold both records since the introduction of electronic timing.[105][106] Furthermore, Bolt became the first sprinter to break both records at the same Olympics.[107] Unlike in the 100 m final, Bolt sprinted hard all the way to the finishing line in the 200 m race, even dipping his chest to improve his time.[108] Following the race, 'Happy Birthday' was played over the stadium's sound system as his 22nd birthday would begin at midnight.[108]

Two days later, Bolt ran as the third leg in the Jamaican 4 × 100 metres relay team, increasing his gold medal total to three.[109] Along with teammates Nesta Carter, Michael Frater, and Asafa Powell, Bolt broke another world and Olympic record, their 37.10 s finish breaking the previous record by three-tenths of a second.[110] Powell, who anchored the team to the finishing line, lamented the loss of his 100m record to Bolt but showed no animosity towards his Jamaican rival, stating that he was delighted to help him set his third world record.[111] In January 2017 the Jamaican relay teammates were stripped of their gold medals when a blood sample taken from Carter after the race was retested and found positive for a banned substance.[112] Following his victories, Bolt donated US$50,000 to the children of Sichuan province in China to help those harmed by the 2008 Sichuan earthquake.[113]

Bolt's record-setting runs caused commentators not only to praise his achievements but to speculate about his potential to become one of the most successful sprinters in history.[23][114] Critics hailed his Olympic success as a new beginning for a sport that had long suffered through high-profile drug scandals.[75][115] The previous six years had seen the BALCO scandal, Tim Montgomery and Justin Gatlin stripped of their 100 m world records, and Marion Jones returning three Olympic gold medals.[116] All three sprinters were disqualified from athletics after drugs tests detected banned substances in their systems.[117][118] Bolt's record-breaking performances caused suspicion among some commentators, including Victor Conte, and the lack of an independent Caribbean anti-doping federation raised more concerns.[119][120] The accusations of drug use were vehemently rejected by Glen Mills (Bolt's coach) and Herb Elliott (the Jamaican athletics team doctor). Elliott, a member of the IAAF anti-doping commission, urged those concerned about the issue to 'come down and see our programme, come down and see our testing, we have nothing to hide'.[121] Mills had been equally ardent that Bolt was a clean athlete, declaring to the Jamaica Gleaner: 'We will test any time, any day, any part of the body...[he] doesn't even like to take vitamins'.[122] Bolt stated that he had been tested four times prior to the Olympics, and all had tested negative for banned substances. He also welcomed anti-doping authorities to test him to prove that he was clean, stating, 'We work hard and we perform well and we know we're clean'.[123]

I was slowing down long before the finish and wasn't tired at all. I could have gone back to the start and done it all over again.

After the 2008 Olympics

At the end of the 2008 athletics season, Bolt competed in the ÅF Golden League, beginning in Weltklasse Zürich. Despite having the slowest start among his competitors in the 100 m race, he still crossed the finishing line in 9.83 s.[125] Even though the time was slower than both his newly set world record and Asafa Powell's track record, it was still among the top-fifteen 100 m finishes by any sprinter to that date.[89] Bolt admitted that he was not running at full strength because he was suffering from a cold, but he concentrated on winning the race and finishing the season in good health.[125] At the Super Grand Prix final in Lausanne, Bolt ran his second-fastest 200 m with a time of 19.63 s, equalling Xavier Carter's track record.[126] However, it was the 100 m final, featuring Asafa Powell, that drew the most interest. Powell had moved closer to Bolt's world record after setting a new personal best of 9.72 s, reaffirming his status as Bolt's main contender.[127] Bolt's final event of the season came three days later at the Golden League final in Brussels. This was the first 100 m race featuring both Bolt and Powell since the final in the Olympics. Both Jamaicans broke the track record, but Bolt came out on top with a time of 9.77 s, beating Powell by 0.06 s. Victory, however, did not come as smoothly as it had in Beijing. Bolt made the slowest start of the nine competitors and had to recover ground in cold conditions and against a 0.9 m/s headwind.[128] Yet the results confirmed Jamaican dominance in the 100 m, with nine of the ten-fastest legal times in history being recorded by either Bolt or Powell.[89]

On his return to Jamaica, Bolt was honoured in a homecoming celebration and received an Order of Distinction in recognition of his achievements at the Olympics.[129] Additionally, Bolt was selected as the IAAF Male Athlete of the year, won a Special Olympic Award for his performances, and was named Laureus World Sportsman of the Year.[130][131] Bolt turned his attention to future events, suggesting that he could aim to break the 400 metres world record in 2010 as no major championships were scheduled that year.[132]

2009 Berlin World Championships

Bolt started the season competing in the 400 metres in order to improve his speed, winning two races and registering 45.54 s in Kingston,[133] and windy conditions gave him his first sub-10 seconds finish of the season in the 100 m in March.[134] In late April Bolt, suffered minor leg injuries in a car crash. However, he quickly recovered following minor surgery and (after cancelling a track meet in Jamaica) he stated that he was fit to compete in the 150 metres street race at the Manchester Great City Games.[135] Bolt won the race in 14.35 s, the fastest time ever recorded for 150 m.[8] Despite not being at full fitness, he took the 100 and 200 m titles at the Jamaican national championships, with runs of 9.86 s and 20.25 s respectively.[136][137] This meant he had qualified for both events at the 2009 World Championships. Rival Tyson Gay suggested that Bolt's 100 m record was within his grasp, but Bolt dismissed the claim and instead noted that he was more interested in Asafa Powell's return from injury.[138] Bolt defied unfavourable conditions at the Athletissima meet in July, running 19.59 seconds into a 0.9 m/s headwind and rain, to record the fourth fastest time ever over 200 m,[139] one hundredth off Gay's best time.[140]

The 2009 World Championships were held during August at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin, which was coincidentally the same month and venue where Jesse Owens had achieved world-wide fame 73 years earlier. Bolt eased through the 100-m heats, clocking the fastest ever pre-final performance of 9.89 seconds.[141] The final was the first time that Bolt and Gay had met during the season, and Bolt set a new world record—which stands to this day—with a time of 9.58s to win his first World Championship gold medal. Bolt took more than a tenth of a second off his previous best mark, and this was the largest-ever margin of improvement in the 100-m world record since the beginning of electronic timing.[7] Gay finished with a time of 9.71 s, 0.02 s off Bolt's 9.69 s world-record run in Beijing.[142][143]

Although Gay withdrew from the second race of the competition, Bolt once again produced world record-breaking time in the 200 metres final. He broke his own record by 0.11 seconds, finishing with a time of 19.19 seconds.[144] He won the 200 m race by the largest margin in World Championships history, even though the race had three other athletes running under 19.90 seconds, the greatest number ever in the event.[9][145] Bolt's pace impressed even the more experienced of his competitors; third-placed Wallace Spearmon complimented his speed,[146] and the Olympic champion in Athens 2004Shawn Crawford said 'Just coming out there...I felt like I was in a video game, that guy was moving – fast'.[147] Bolt pointed out that an important factor in his performance at the World Championships was his improved start to the races: his reaction times in the 100 m (0.146)[148] and 200 m (0.133)[149] were significantly faster than those he had produced in his world record runs at the Beijing Olympics.[150][151] However, he, together with other members of Jamaican 4×100 m relay team, fell short of their own world record of 37.10 s set at 2008 Summer Olympics by timing 37.31 s, which is, however, a championship record and the second fastest time in history at that date.[152]

On the last day of the Berlin Championships, the Governing Mayor of Berlin, Klaus Wowereit, presented Bolt with a 12-foot high section of the Berlin Wall in a small ceremony, saying Bolt had shown that 'one can tear down walls that had been considered as insurmountable.'[153] The nearly three-ton segment was delivered to the Jamaica Military Museum in Kingston.[154]

Several days after Bolt broke the world records in 100 and 200 metres events, Mike Powell, the world record holder in long jump (8.95 metres set in 1991) argued that Bolt could become the first man to jump over 9 metres, the long jump event being 'a perfect fit for his speed and height'.[155] At the end of the season, he was selected as the IAAF World Athlete of the Year for the second year running.[156]

2010 Diamond League and broken streak

Early on in the 2010 outdoor season, Bolt ran 19.56 seconds in the 200 m in Kingston, Jamaica for the fourth-fastest run of all-time, although he stated that he had no record breaking ambitions for the forthcoming season.[157] He took to the international circuit May with wins in East Asia at the Colorful Daegu Pre-Championships Meeting and then a comfortable win in his 2010 IAAF Diamond League debut at the Shanghai Golden Grand Prix.[158][159] Bolt made an attempt to break Michael Johnson's best time over the rarely competed 300 metres event at the Golden Spike meeting in Ostrava. He failed to match Johnson's ten-year-old record of 30.85 and suffered a setback in that his 30.97-second run in wet weather had left him with an Achilles tendon problem.[160][161]

After his return from injury a month later, Bolt asserted himself with a 100 m win at the Athletissima meeting in Lausanne (9.82 seconds) and a victory over Asafa Powell at Meeting Areva in Paris (9.84 seconds).[162][163] Despite this run of form, he suffered only the second loss of his career in a 100 m final at the DN Galan. Tyson Gay soundly defeated him with a run of 9.84 to Bolt's 9.97 seconds, and the Jamaican reflected that he had slacked off in training early in the season while Gay had been better prepared and in a better condition.[164] This marked Bolt's first loss to Gay in the 100 m, which coincidentally occurred in the same stadium where Powell had beaten Bolt for the first time two years earlier.[165]

2011 World Championships

Bolt went undefeated over 100 m and 200 m in the 2011 season. He began with wins in Rome and Ostrava in May.[166] He ran his first 200 m in over a year in Oslo that June and his time of 19.86 seconds was a world-leading one. Two further 200 m wins came in Paris and Stockholm the following month, as did a 100 m in Monaco, though he was a tenth of a second slower than compatriot Asafa Powell before the world championships.[167]

Considered the favourite to win in the 100 metres at the 2011 World Championships in Daegu, Bolt was eliminated from the final, breaking 'ridiculously early' according to the starter in an interview for BBC Sport, and receiving a false start.[168] This proved to be the highest profile disqualification for a false start since the IAAF changed the rules that previously allowed one false start per race. The disqualification caused some to question the new rule, with former world champion Kim Collins saying it was 'a sad night for athletics'. Usain Bolt's countryman, Yohan Blake, won in a comparatively slow 9.92 seconds.[169]

In the World Championships 200 m, Bolt cruised through to the final which he won in a time of 19.40.[170] Though this was short of his world record times of the two previous major tournaments, it was the fourth fastest run ever at that point, after his own records and Michael Johnson's former record, and left him three tenths of a second ahead of runner-up Walter Dix. This achievement made Bolt one of only two men to win consecutive 200 m world titles, alongside Calvin Smith.[171] Bolt closed the championships with another gold with Jamaica in the 4 × 100 metres relay. Nesta Carter and Michael Frater joined world champions Bolt and Blake to set a world record time of 37.04.[172]

Following the World Championships, Bolt ran 9.85 seconds for the 100 m to win in Zagreb before setting the year's best time of 9.76 seconds at the Memorial Van Damme. This run was overshadowed by Jamaican rival Blake's unexpected run of 19.26 seconds in the 200 m at the same meeting, which brought him within seven hundredths of Bolt's world record.[173] Although Bolt failed to win the Diamond Race in a specific event, he was not beaten on the 2011 IAAF Diamond League circuit, taking three wins in each of his specialities that year.[166][166][174]

2012 Summer Olympics

Bolt began the 2012 season with a leading 100 m time of 9.82 seconds in May.[175] He defeated Asafa Powell with runs of 9.76 seconds in Rome and 9.79 in Oslo.[176] At the Jamaican Athletics Championships, he lost to Yohan Blake, first in the 200 m and then in the 100 m, with his younger rival setting leading times for the year.[177][178]

However, at the 2012 London Olympics, he won the 100 metres gold medal with a time of 9.63 seconds, improving upon his own Olympic record and duplicating his gold medal from the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Blake was the silver medallist with a time of 9.75 seconds.[179][180] Following the race, seventh-place finisher Richard Thompson of Trinidad and Tobago declared 'There's no doubt he's the greatest sprinter of all time', while USA Today referred to Bolt as a Jamaican 'national hero', noting that his victory came just hours before Jamaica was to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its independence from the United Kingdom.[181] With his 2012 win, Bolt became the first man to successfully defend an Olympic sprint title since Carl Lewis in 1988.[182]

I'm now a legend. I'm also the greatest athlete to live.

Bolt followed this up with a successful defence of his Olympic 200 metres title with a time of 19.32 seconds, followed by Blake at 19.44 and Warren Weir at 19.84 to complete a Jamaican podium sweep. With this, Bolt became the first man in history to defend both the 100 m and 200 m Olympic sprint titles.[184][185] He was dramatic in victory: in the final metres of the 200 m race, Bolt placed his fingers on his lips, gesturing to silence his critics, and after crossing the line he completed five push-ups – one for each of his Olympic gold medals.[183][186][187]

On the final day of the 2012 Olympic athletics, Bolt participated in Jamaica's gold medal-winning 4×100 metres relay team along with Nesta Carter, Michael Frater and Blake. With a time of 36.84 seconds, they knocked two tenths of a second from their previous world record from 2011.[188] He celebrated by imitating the 'Mobot' celebration of Mo Farah, who had claimed a long-distance track double for the host nation.[189]

International Olympic Committee (IOC) President Jacques Rogge initially stated that Bolt was not yet a 'legend' and would not deserve such acclaim until the end of his career,[190] but later called him the best sprinter of all time.[191] Following the Olympics he was confirmed as the highest earning track and field athlete in history.[192]

Bolt ended his season with wins on the 2012 IAAF Diamond League circuit; he had 200 m wins of 19.58 and 19.66 in Lausanne and Zürich before closing with a 100 m of 9.86 in Brussels.[193][194] The latter run brought him his first Diamond League title in the 100 m.[195]

2013 World Championships

Bolt failed to record below 10 seconds early season and had his first major 100 m race of 2013 at the Golden Gala in June. He was served an unexpected defeat by Justin Gatlin, with the American winning 9.94 to Bolt's 9.95. Bolt denied the loss was due to a hamstring issue he had early that year and Gatlin responded: 'I don't know how many people have beaten Bolt but it's an honour'.[196][197] With Yohan Blake injured, Bolt won the Jamaican 100 m title ahead of Kemar Bailey-Cole and skipped the 200 m, which was won by Warren Weir.[198][199] Prior to the 2013 World Championships in Athletics, Bolt set world leading times in the sprints, with 9.85 for the 100 m at the London Anniversary Games and 19.73 for the 200 m in Paris.[200][201]

Bolt regained the title as world's fastest man by winning the World Championships 100 metres in Moscow. In wet conditions, he edged Gatlin by eight hundredths of a second with 9.77, which was the fastest run that year.[202][203] Gatlin was the sole non-Jamaican in the top five, with Nesta Carter, Nickel Ashmeade and Bailey-Cole finishing next.[204]

Bolt was less challenged in the 200 m final. His closest rival was Jamaican champion Warren Weir but Bolt ran a time of 19.66 to finish over a tenth of a second clear.[205] This performance made Bolt the first man in the history of the 200 metres at the World Championships in Athletics to win three gold medals over the distance.[206]

Bolt won a third consecutive world relay gold medal in the 4 × 100 metres relay final, which made him the most successful athlete in the 30-year history of the world championships.[207] The Jamaican team, featuring four of the top five from the 100 m final were comfortable winners with Bolt reaching the finish line on his anchor leg three tenths of a second ahead of the American team anchored by Gatlin.[208] Bolt's performances were matched on the women's side by Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, meaning Jamaica took a complete sweep of the sprint medals at the 2013 World Championships.[207]

After the championships, Bolt took 100 m wins on the 2013 IAAF Diamond League circuit in Zürich and Brussels. He remained unbeaten in the 200 m and his only loss that year was to Gatlin over 100 m in Rome.[209] For the fifth time in six years, Bolt was named IAAF World Male Athlete of the Year.[210]

2014: Injury and Commonwealth Games

An injury to Bolt's hamstring in March 2014 caused him to miss nine weeks of training. Having recovered from surgery, Bolt competed in the 4 × 100 metres relay of the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow. Not in peak form Bolt said that he was attending the Games for the fans and to show his progress since the injury.[211] Bolt and his teammates won the 4 × 100 metres relay in 37.58 seconds – a Commonwealth Games record.[212] This was the foremost competition of the year for Bolt, given no Olympics or World Championships in 2014.

In August 2014, Bolt set the indoor 100 m world record in Warsaw with a time of 9.98 seconds.[213] This was his sole individual outing of the 2014 season.[214] Soon afterwards he ended his season early in order to be fit for the 2015 season.[215] In Bolt's absence, Justin Gatlin had dominated the sprints, holding the year's fastest times, including seven of the top ten 100 m runs that season.[214][216]

2015 Beijing World Championships

At the start of 2015, he announced that he intended to make the 2017 World Championships in Athletics his last major competition before retirement.[217]

Upon his return from injury, Bolt appeared a reduced figure at the start of the 2015 season. He ran only two 100 m and three 200 m before the major championship. He opened with 10.12 seconds for the 100 m and 20.20 for the 200 m. He won the 200 m in New York and Ostrava, but his season's best time of 20.13 seconds ranked him 20th in the world going into the championships.[218] Two 100 m runs of 9.87 in July in London showed better form, but in comparison, Justin Gatlin was easily the top ranked sprinter – the American had times of 9.74 and 19.57 seconds, and had already run under 9.8 seconds on four occasions that season.[218][219] Bolt entered the World Championships to defend his sprint titles but was not the comfortable favourite he had been since 2008.[220][221]

In the World Championships 100 m, Bolt won his semi-final in 9.96, which lagged Gatlin's semi-final win in 9.77 seconds.[219] However, Gatlin did not match that form in the final while Bolt improved through the rounds. In a narrow victory, Bolt leaned at the line to beat Gatlin 9.79 to 9.80 seconds. Bolt joined Carl Lewis and Maurice Greene on a record three 100 m world titles.[222][223][224]

A similar outcome followed in the 200 m World finals. In the semi-final, Gatlin outpaced Bolt – the Jamaican at 19.95 and the American at 19.87. Despite such slow times prior to Beijing, Bolt delivered in the final with his fifth fastest run ever for the 200 m at 19.55 seconds. Gatlin failed to reach his early season form and finished almost two-tenths of a second behind Bolt. Bolt's four consecutive wins over 200 m at the World Championships was unprecedented and established him clearly as the best ever sprinter at the competition.[225]

There was also a fourth straight win in the 4 × 100 metres relay with the Jamaica team (Nesta Carter, Asafa Powell, Nickel Ashmeade, Usain Bolt). The Americans initially had a lead, but a poor baton exchange saw them disqualified and Jamaica defend their title in 37.36 seconds – well clear of the Chinese team who took a surprise silver for the host nation.[226]

Conscious of his injuries at the start of the season, he did not compete after the World Championships, skipping the 2015 IAAF Diamond League final.[227]

2016 Rio Olympics

Bolt competed sparingly in the 200 m before the Olympics, with a run of 19.89 seconds to win at the London Grand Prix being his sole run of note over that distance. He had four races over 100 m, though only one was in Europe, and his best of 9.88 seconds in Kingston placed him fourth on the world seasonal rankings. As in the previous season, Gatlin appeared to be in better form, having seasonal bests of 9.80 and 19.75 seconds to rank first and second in the sprints.[228][229]Doping in athletics was a prime topic before the 2016 Rio Olympics, given the banning of the Russian track and field team for state doping, and Bolt commented that he had no problem with doping controls: 'I have no issue with being drug-tested...I remember in Beijing every other day they were drug-testing us'. He also highlighted his dislike of rival Tyson Gay's reduced ban for cooperation, given their close rivalry since the start of Bolt's career, saying 'it really bothered me – really, really bothered me'.[230]

I want to be among greats Muhammad Ali and Pelé.

At the 2016 Rio Olympics, Bolt won the 100 metres gold medal with a time of 9.81 seconds.[232] With this win, Bolt became the first athlete to win the event three times at the Olympic Games.[232] Bolt followed up his 100 m win with a gold medal in the 200 m, which also makes him the first athlete to win the 200 m three times at the Olympic Games.[233] Bolt ran the anchor leg for the finals of the 4 × 100 m relay and secured his third consecutive and last Olympic gold medal in the event.[234] With that win, Bolt obtained the 'triple-triple', three sprinting gold medals in three consecutive Olympics, and finished his Olympic career with a 100% win record in finals.[234] However, in January 2017, Bolt was stripped of the 4 × 100 relay gold from the Beijing Games in 2008 because his teammate Nesta Carter was found guilty of a doping violation.[235]

2017 season

Bolt took a financial stake in a new Australia-based track and field meeting series – Nitro Athletics. He performed at the inaugural meet in February 2017 and led his team (Bolt All-Stars) to victory. The competition featured variations on traditional track and field events. He committed himself to three further editions.[236][237]

In 2017, the Jamaican team was stripped of the 2008 Olympics 4×100 metre title due to Nesta Carter's disqualification for doping offences. Bolt, who never failed a dope test, was quoted by the BBC saying that the prospect of having to return the gold was 'heartbreaking'.[238] The banned substance in Carter's test was identified as methylhexanamine, a nasal decongestant sometimes used in dietary supplements.

At the 2017 World Athletics Championships, Bolt won his heat uncomfortably after a slow start in 10.07, in his semi-final he improved to 9.98 but was beaten by Christian Coleman by 0.01. That race broke Bolt's 4 year winning streak in the 100 m. In his final individual race, in the final, Bolt won the Bronze medal in 9.95, 0.01 behind Silver medalist Coleman and 0.03 behind World Champion Justin Gatlin. It was the first time Bolt had been beaten at a major championship since the 4×100 m relay of the 2007 World Athletics Championships. Also at the 2017 World Athletics Championships, Bolt participated as the anchor runner for Jamaica's 4×100-metre relay team in both the heats and the final. Jamaica won their heat comfortably in 37.95 seconds. In what was intended to be his final race, Bolt pulled up in agony with 50 metres to go and collapsed to the track after what was later confirmed to be another hamstring injury. He refused a wheelchair and crossed the finish line one last time with the assistance of his teammates Omar McLeod, Julian Forte, and Yohan Blake.[239]

Football career

In an interview with Decca Aitkenhead of The Guardian in November 2016, Bolt said he wished to play as a professional footballer after retiring from athletics. He reiterated his desire to play for Manchester United if given a chance and added, 'For me, if I could get to play for Manchester United, that would be like a dream come true. Yes, that would be epic'.[240]

In 2018, after training with Norwegian side Strømsgodset,[241] Bolt played for the club as a forward in a friendly match against the Norway national under-19 team. He wore the number '9.58' in allusion to his 100 m world record.[242] Bolt wore the same number whilst captaining the World XI during Soccer Aid 2018 at Old Trafford.[243]

On 21 August 2018, on his 32nd birthday, Bolt started training with Australian club Central Coast Mariners of the A-League.[244] He made his friendly debut for the club as a substitute on 31 August 2018 against a Central Coast Select team, made up of players playing in the local area.[245] On 12 October, he started in a friendly against amateur club Macarthur South West United and scored two goals, both in the second half, with his goal celebration featuring his signature “To Di World” pose.[246][247]

Bolt was offered a two-year contract from Maltese club Valletta, which he turned down on 18 October 2018.[248] On 21 October 2018, Bolt was offered a contract by the Mariners.[249] The Australian FA was helping the Mariners to fund it.[250] Later that month, Perth Glory forward Andy Keogh was critical of Bolt's ability, stating his first touch is 'like a trampoline'. He added Bolt has 'shown a bit of potential but it's a little bit of a kick in the teeth to the professionals that are in the league.'[251]

Bolt left the Mariners in early November 2018 after 8 weeks with the club.[252] In January 2019, Bolt announced that he would not be pursuing a career in football, saying his 'sports life is over'.[253]

Personal life

Bolt expresses a love for dancing and his character is frequently described as laid-back and relaxed.[25][254] His Jamaican track and field idols include Herb McKenley and former Jamaican 100 m and 200 m world record holder, Don Quarrie. Michael Johnson, the former 200 m world and Olympic record holder, is also held in high esteem by Bolt.[25]

Bolt has the nickname 'Lightning Bolt' due to his name and speed.[1] He is Catholic and known for making the sign of the cross before racing competitively, and he wears a Miraculous Medal during his races. His middle name is St. Leo.[255]

In 2010, Bolt also revealed his fondness of music, when he played a reggae DJ set to a crowd in Paris.[256] He is also an avid fan of the Call of Duty video game series, saying, 'I stay up late [playing the game online], I can't help it.'[257]

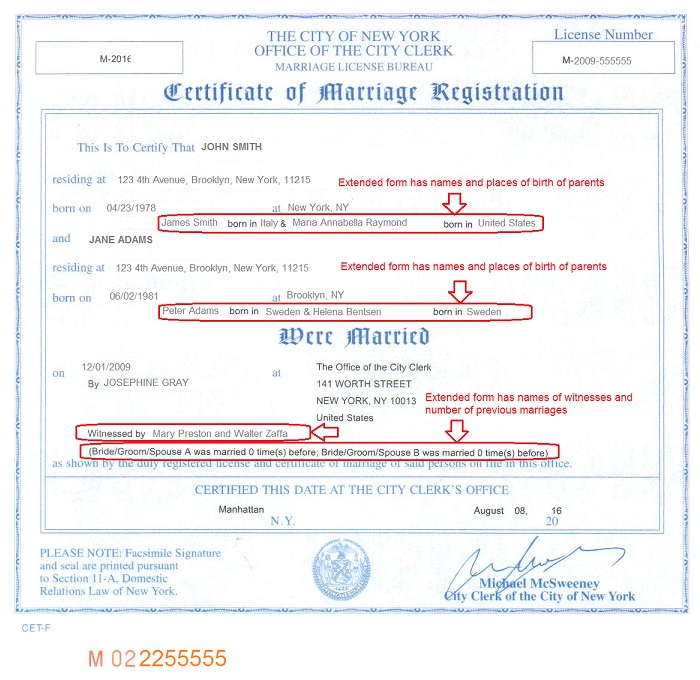

What Does A Jamaican Marriage License Look Like

In his autobiography, Bolt reveals that he has suffered from scoliosis, a condition that has curved his spine to the right and has made his right leg half an inch shorter than his left.[258]

He popularised the 'lightning bolt' pose, also known as 'to di world' or 'bolting', which he used both before races and in celebration. The pose consists of extending a slightly raised left arm to the side and the right arm folded across the chest, with both hands have the thumb and index finger outstretched. His performance of the pose during his Olympic and World Championship victories led to widespread copying of the move, from American President Barack Obama to small children. It has been suggested that the pose comes from Jamaican dancehall moves of the period,[259][260] though Olympic sprint champion Bernard Williams also had performed similar celebration moves earlier that decade.[261]

Other sports

Cricket was the first sport to interest Bolt, and he said if he were not a sprinter, he would be a fast bowler instead.[25] As a child, he was a supporter of the Pakistani cricket team and admired the bowling of Waqar Younis.[262] He is also a fan of Indian batsman Sachin Tendulkar, West Indian opener Chris Gayle,[263] and Australian opener Matthew Hayden.[264] During a charity cricket match, Bolt clean-bowled Gayle who was complimentary of Bolt's pace and swing.[265] Bolt also struck a six off Gayle's bowling. Another bowler complimentary of Bolt's pace was former West Indies fast-bowling great Curtly Ambrose.[266]

After talking with Australian cricketer Shane Warne, Bolt suggested that if he were able to get time off he would be interested in playing in the cricket Big Bash League. Melbourne Stars chief executive Clint Cooper said there were free spots on his team should be available. Bolt stated that he enjoyed the Twenty20 version of the game, admiring the aggressive and constant nature of the batting. On his own ability, he said 'I don't know how good I am. I will probably have to get a lot of practice in.'[267][268]

Bolt is also a fan of Premier League football team Manchester United.[269] He has declared he is a fan of Dutch striker Ruud van Nistelrooy.[270] Bolt was a special guest of Manchester United at the 2011 UEFA Champions League Final in London, where he stated that he would like to play for them after his retirement.[271]

In 2013, Bolt played basketball in the NBA All-Star Weekend Celebrity Game. He scored two points from a slam dunk but acknowledged his other basketball skills were lacking.[272]

Biographical film

A biographical film based on the athletic life of Bolt to win three Olympic gold medals, titled I Am Bolt, was released on 28 November 2016 in United Kingdom. The film was directed by Benjamin Turner and Gabe Turner.[273][274]

Sponsorships and advertising work

After winning the 200 m title in the 2002 World Junior Championships in Kingston, Bolt signed a sponsorship deal with Puma.[275] To promote Bolt's chase for Olympic glory in the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, China, Puma released a series of videos including Bolt's then-world-record-setting run in Icahn Stadium and his Olympic preparations.[276] After his world record breaking run in New York City, which was preceded by a lightning storm,[277] the press frequently made puns on the Jamaican's name, nicknaming him 'Lightning Bolt' and the 'Bolt from the blue'.[278][279][280] During the 2008 Beijing 100 m final, Bolt wore golden Puma Complete Theseus spikes that had 'Beijing 100 m Gold' emblazoned across them.[281] Writing of Bolt's performance at the Olympics, The Associated Press said:

Almost single-handedly, Bolt has helped track transform itself from a dying sport to one with a singular, smiling, worldwide star.

In September 2010, Bolt travelled to Australia where his sponsor Gatorade was holding an event called the 'Gatorade Bolt' to find Australia's fastest footballer. The event was held at the Sydney International Athletic Centre and featured football players from rugby league, rugby union, Australian rules football, and association football. Prior to the race Bolt gave the runners some private coaching and also participated in the 10th anniversary celebrations for the 2000 Summer Olympic Games.[282]

In January 2012, Bolt impersonated Richard Branson in an advertising campaign for Virgin Media.[283] The campaign was directed by Seth Gordon and features the Virgin founder Branson to promote its broadband service. In March 2012, Bolt starred in an advert for Visa and the 2012 Summer Olympics.[284] In July 2012, Bolt and RockLive launched Bolt!, an Apple iOS game based on his exploits. Bolt! quickly became the No. 1 app in Jamaica and climbed the UK iTunes charts to reach No. 2 on the list of Top Free Apps.[285]

Bolt's autobiography, My Story: 9.58: Being the World's Fastest Man, was released in 2010. Bolt had previously said that the book '...should be exciting, it's my life, and I'm a cool and exciting guy.'[269] His athletics agent is PACE Sports Management.[286]

As part of his sponsorship deal with Puma, the manufacturer sends sporting equipment to his alma mater, William Knibb Memorial High School, every year. At Bolt's insistence, advertisements featuring him are filmed in Jamaica, by a Jamaican production crew, in an attempt to boost local enterprise and gain exposure for the country.[287] In 2017, Bolt had the third highest earning social media income for sponsors among sportspeople (behind Cristiano Ronaldo and Neymar), and he was the only non-footballer in the top seven.[288]

Recognition

- IAAF World Athlete of the Year: 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2016[289]

- Track & Field Athlete of the Year: 2008, 2009

- Laureus World Sportsman of the Year: 2009, 2010, 2013, 2017[290][291][292]

- BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year: 2008, 2009, 2012

- L'Équipe Champion of Champions: 2008, 2009, 2012, 2015

- Jamaica Sportsman of the year: 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013

- AIPS Male Athlete of the Year: 2015[293]

- Marca Leyenda(2009)

- In October 2008, he was made a Commander of the Order of Distinction,[294] which entitles him to use the post nominal letters CD.[295]

- In 2009, at age 23, Usain Bolt became the youngest member so far[296] of the Order of Jamaica.[297][298] The award was 'for outstanding performance in the field of athletics at the international level'.[296] In the Jamaican honours system, this is considered the equivalent of a knighthood in the British honours system,[299] and entitles him to be formally styled 'The Honourable', and to use the post nominal letters OJ.[295]

Personal appearances

Bolt made a cameo appearance in the opening sketch of 13 October 2012 broadcast of Saturday Night Live, hosted by Christina Applegate. The segment was a parody of the Vice Presidential debate between Joe Biden and Paul Ryan. In the sketch, Taran Killam mimicking Ryan had just lied about running a 2:50 marathon, a sub-4-minute mile on no training and winning the 100 metres in London when Bolt was introduced as his partner to confirm.

When Ryan asked Bolt 'Who won the 100 metres?' the Jamaican gold-medallist answered simply. 'I did.' Ryan followed up by asking Bolt about his (Ryan's) finish. 'You didn't finish. You weren't even there.'[300][301]

On 23 November 2016, Bolt competed against James Corden in a rap battle on the 'Drop the Mic' segment of The Late Late Show with James Corden, which he won.

Statistics

Personal bests

| Event | Time (seconds) | Venue | Date | Records | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 metres | 9.58 | Berlin, Germany | 16 August 2009 | WR | Also has the second fastest time (9.63) and shares the third fastest time of 9.69 with Tyson Gay and Yohan Blake. Bolt's 9.63 is the Olympic record, set at the 2012 games. |

| 150 metres | 14.35 | Manchester, United Kingdom | 17 May 2009 | WB[note 2] | He ran the last 100 m in 8.70, the fastest ever recorded time over a 100 m distance. This would equal an average speed of 41.38 km/h (25.71 mph). |

| 200 metres | 19.19 | Berlin, Germany | 20 August 2009 | WR | Also holds the Olympic record with 19.30, which was then (2008) a world record. |

| 300 metres | 30.97 | Ostrava, Czech Republic | 27 May 2010 | NR | This is the third fastest time, behind Wayde van Niekerk 30.81 & Michael Johnson 30.85A. The event is not recognised by the IAAF. |

| 400 metres | 45.28 | Kingston, Jamaica | 5 May 2007 | [1] | |

| 4 × 100 metres relay | 36.84 | London, England | 11 August 2012 | WR | Shared with Yohan Blake, Michael Frater and Nesta Carter. |

Records

Bolt's personal best of 9.58 seconds in 2009 in the 100 metres is the fastest ever run.[302] Bolt also holds the second fastest time of 9.63 seconds,[87] the current Olympic record,[89] and set two previous world records in the event. Bolt's personal best of 19.19 s in the 200 metres is the world record. This was recorded at the 2009 World Championships in Athletics in Berlin against a headwind of −0.3 m/s. This performance broke his previous world record in the event, his 19.30 s clocking in winning the 2008 Olympic 200 metres title.

Bolt has been on three world-record-setting Jamaican relay teams. The first record, 37.10 seconds, was set in winning gold at the 2008 Summer Olympics, although the result was voided in 2017 when the team was disqualified. The second record came at the 2011 World Championships in Athletics, a time of 37.04 seconds. The third world record was set at the 2012 Summer Olympics, a time of 36.84 seconds.[303]

Bolt also holds the 200 metres world teenage best results for the age categories 15 (20.58 s), 16 (20.13 s, world youth record), 17 (19.93 s) and 18 (19.93 s, world junior record).[87] He also holds the 150 metres world best set in 2009, during which he ran the last 100 metres in 8.70 seconds, the quickest timed 100 metres ever.[87]

Bolt completed a total of 53 wind-legal sub-10-second performances in the 100 m during his career, with his first coming on 3 May 2008 and his last on 5 August 2017 at the World Championships. His longest undefeated streak in the 200 m was in 17 finals, lasting from 12 June 2008 to 3 September 2011. He also had a win-streak covering 14 100 m finals from 16 August 2008 to 16 July 2010.[304]

Guinness World Records

Bolt claimed 19 Guinness World Records, and, after Michael Phelps, holds second highest number of accumulative Guinness World Records for total number of accomplishments and victories in the sport.[305]

- Fastest run 150 metres (male)

- Most medals won at the IAAF Athletics World Championships (male)

- Most gold medals won at the IAAF Athletics World Championships (male)

- Most Athletics World Championships Men’s 200 m wins

- Most consecutive Olympic gold medals won in the 100 metres (male)

- Most consecutive Olympic gold medals won in the 200 metres (male)

- Most Olympic men’s 200 metres Gold medals

- Fastest run 200 metres (male)

- Most Men’s IAAF World Athlete of Year Trophies

- First Olympic track sprint triple-double

- Highest annual earnings for a track athlete

- Most wins of the 100 m sprint at the Olympic Games

- First athlete to win the 100 m and 200 m sprints at successive Olympic Games

- Fastest run 100 metres (male)

- First man to win the 200 m sprint at successive Olympic Games

- Most Athletics World Championships Men’s 100 m wins

- Most tickets sold at an IAAF World Championships

- Most competitive 100 m sprint races completed in sub 10 seconds

- Fastest relay 4×100 metres (male)

Average and top speeds

From his record time of 9.58 s for the 100 m sprint, Usain Bolt's average ground speed equates to 37.58 km/h (23.35 mph). However, once his reaction time of 0.148 s is subtracted, his time is 9.44 s, making his average speed 38.18 km/h (23.72 mph).[306] Bolt's top speed, based on his split time of 1.61 s for the 20 metres from the 60- to 80-metre marks (made during the 9.58 WR at 100m), is 12.42 m/s (44.72 km/h (27.79 mph)).[307]

Season's bests

World rank in parentheses

| Year | 100 metres | 200 metres | 400 metres |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | — | 21.73 | 48.28 |

| 2002 | — | 20.58 | 47.12 |

| 2003 | — | 20.13 (9) | 45.35 |

| 2004 | — | 19.93 (2) | 47.58 |

| 2005 | — | 19.99 (3) | — |

| 2006 | — | 19.88 (4) | 47.58 |

| 2007 | 10.03 (12) | 19.75 (3) | 45.28 |

| 2008 | 9.69 (1) | 19.30 (1) | 46.94 |

| 2009 | 9.58 (1) | 19.19 (1) | 45.54 |

| 2010 | 9.82 (4) | 19.56 (1) | 45.87 |

| 2011 | 9.76 (1) | 19.40 (2) | — |

| 2012 | 9.63 (1) | 19.32 (1) | — |

| 2013 | 9.77 (2) | 19.66 (1) | 46.44 |

| 2014 | 9.98 (16) | — | — |

| 2015 | 9.79 (2) | 19.55 (1) | 46.38 |

| 2016 | 9.81 (2) | 19.78 (3) | — |

| 2017 | 9.95 (10) | — | — |

International competitions

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | CARIFTA Games | Bridgetown, Barbados | 2nd | 200 m | 21.81 |

| 2nd | 400 m | 48.28 | |||

| World Youth Championships | Debrecen, Hungary | 5th (semi 2) | 200 m | 21.73 | |

| 4th | Medley relay | 1:52.36 | |||

| 2002 | CAC Junior Championships (U17) | Bridgetown, Barbados | 1st | 200 m | 20.61 CR |

| 1st | 400 m | 47.12 CR | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 40.95 CR | |||

| 1st | 4×400 m relay | 3:16.61 CR | |||

| CARIFTA Games | Nassau, Bahamas | 1st | 200 m | 21.12 CR | |

| 1st | 400 m | 47.33 CR | |||

| 1st | 4×400 m relay | 3:18.88 CR | |||

| World Junior Championships | Kingston, Jamaica | 1st | 200 m | 20.61 | |

| 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 39.15 NJR | |||

| 2nd | 4×400 m relay | 3:04.06 NJR | |||

| 2003 | CARIFTA Games | Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago | 1st | 200 m | 20.43 CR |

| 1st | 400 m | 46.35 CR | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 39.43 CR | |||

| 1st | 4×400 m relay | 3:09.70 | |||

| World Youth Championships | Sherbrooke, Canada | 1st | 200 m | 20.40 | |

| DNS (semi 1) | 400 m | ||||

| DQ (semi 2) | Medley relay | ||||

| Pan American Junior Championships | Bridgetown, Barbados | 1st | 200 m | 20.13 WYB | |

| 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 39.40 | |||

| 2004 | CARIFTA Games | Hamilton, Bermuda | 1st | 200 m | 19.93 WJR |

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 39.48 | |||

| 1st | 4×400 m relay | 3:12.00 | |||

| Olympic Games | Athens, Greece | 5th (heat 4) | 200 m | 21.05 | |

| 2005 | CAC Championships | Nassau, Bahamas | 1st | 200 m | 20.03 |

| World Championships | Helsinki, Finland | 8th | 200 m | 26.27 | |

| 2006 | World Athletics Final | Stuttgart, Germany | 3rd | 200 m | 20.10 |

| IAAF World Cup | Athens, Greece | 2nd | 200 m | 19.96 | |

| 2007 | World Championships | Osaka, Japan | 2nd | 200 m | 19.91 |

| 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 37.89 | |||

| 2008 | Olympic Games | Beijing, China | 1st | 100 m | 9.69 WROR |

| 1st | 200 m | 19.30 WROR | |||

| DQ | 4×100 m relay | Doping[308] | |||

| 2009 | World Championships | Berlin, Germany | 1st | 100 m | 9.58 WRCR |

| 1st | 200 m | 19.19 WRCR | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 37.31 CR | |||

| World Athletics Final | Thessaloniki, Greece | 1st | 200 m | 19.68 =CR | |

| 2011 | World Championships | Daegu, South Korea | DQ | 100 m | False start |

| 1st | 200 m | 19.40 WL | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 37.04 WRCR | |||

| 2012 | Olympic Games | London, United Kingdom | 1st | 100 m | 9.63 OR |

| 1st | 200 m | 19.32 | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 36.84 WR | |||

| 2013 | World Championships | Moscow, Russia | 1st | 100 m | 9.77 |

| 1st | 200 m | 19.66 | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 37.36 | |||

| 2014 | Commonwealth Games | Glasgow, United Kingdom | 1st | 4×100 m relay | 37.58 GR |

| 2015 | World Relays | Nassau, Bahamas | 2nd | 4×100 m relay | 37.68 |

| World Championships | Beijing, China | 1st | 100 m | 9.79 | |

| 1st | 200 m | 19.55 WL | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 37.36 WL | |||

| 2016 | Olympic Games | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 1st | 100 m | 9.81 |

| 1st | 200 m | 19.78 | |||

| 1st | 4×100 m relay | 37.27 | |||

| 2017 | World Championships | London, United Kingdom | 3rd | 100 m | 9.95 |

| DNF | 4×100 m relay | Injury |

National titles

- Jamaican Athletics Championships

- 100 m: 2008, 2009, 2013

- 200 m: 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009

Circuit wins

- 2012 IAAF Diamond League (100 metres)

- 100 m

- Vardinoyiannia: 2007

- Kingston Jamaica Invitational: 2008, 2012

- New York Grand Prix: 2008

- Hampton International Games: 2008

- Weltklasse Zürich: 2008, 2009, 2013

- Memorial Van Damme: 2008, 2011, 2012, 2013

- Ostrava Golden Spike: 2009, 2011, 2012, 2016, 2017

- Meeting Areva: 2009, 2010

- London Grand Prix: 2009, 2013, 2015

- Colorful Daegu Championships Meeting: 2010

- Athletissima: 2010

- Golden Gala: 2011, 2012

- Herculis: 2011, 2017

- Hanžeković Memorial: 2011

- Kingston Racers Grand Prix: 2016, 2017

- 200 m

- New York Grand Prix: 2005, 2015

- Kingston Jamaica Invitational: 2005, 2006, 2010

- Ostrava Golden Spike: 2006, 2008, 2015

- Hanžeković Memorial: 2006

- London Grand Prix: 2007, 2008, 2016

- Hampton International Games: 2007

- Athens Grand Prix Tsiklitiria: 2008

- Athletissima: 2008, 2009, 2012

- Memorial Van Damme: 2009

- Shanghai Golden Grand Prix: 2010

- Bislett Games: 2011, 2012, 2013

- Meeting Areva: 2011, 2013

- DN Galan: 2011

- Weltklasse Zürich: 2012

- Warszawa Kamila Skolimowska Memorial: 2014

- Kingston Utech Classic: 2015

- 300 m

- Ostrava Golden Spike: 2010

See also

Notes

- ^Not a competition event.

- ^ abThis is not an official world record as the IAAF, the international athletics governing body, does not recognise the distance.

References

- ^ abcdefghijklmnoLawrence, Hubert; Samuels, Garfield (20 August 2007). 'Focus on Jamaica – Usain Bolt'. Focus on Athletes. International Association of Athletics Federations. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^Thomas, Claire. 'Built for speed: what makes Usain Bolt so fast?'. telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^'Usain BOLT'. usainbolt.com. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^Thomas, Claire (25 July 2016). 'Glen Mills: the man behind Usain Bolt's record-shattering career'. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^Wile, Rob (11 August 2017). 'Usain Bolt Is Retiring. Here's How He Made Over $100 Million in 10 Years'. Money. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^Clark, Nate (2 February 2019). 'Usain Bolt having fun at Super Bowl, 'ties' NFL Combine 40-yard dash record'. NBC. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ abClarey, Christopher (16 August 2009). Bolt Shatters 100-Meter World Record Archived 29 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ ab'Bolt runs 14.35 sec for 150m; covers 50m-150m in 8.70 sec!'. International Association of Athletics Federations. 17 May 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ abHart, Simon (20 August 2009). World Athletics: Usain Bolt breaks 200 metres world record in 19.19 secondsArchived 21 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ abcdefgh'Usain Bolt IAAF profile'. IAAF. Archived from the original on 18 August 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^'Sports Illustrated'. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^Ellington, Barbara (31 August 2008). He is a happy person, says Usain's mother. Jamaica Gleaner. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- ^'Usain Bolt's Olympic goodbye the perfect ending for sprinting's greatest'. The Guardian. 21 August 2016. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016.

- ^'Bolt completes triple-triple, proves he's greatest sprinter of all time' (20 August 2016). The News & Observer. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017.

- ^'Usain Bolt wins gold in his LAST Olympic race: He cements his legacy as the greatest sprinter in history as he makes it nine gold medals out of nine with 4x100m relay victory'. Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^'Usain Bolt is the best of all time says Michael Johnson'. BBC. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016.

- ^Reuters, Thomson (16 May 2019). 'Bolt unveils new electric scooter model in Paris Reuters.com'. U.S. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^Ferdinand, Rio (1 February 2009). 'Local heroes: Usain BoltArchived 28 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine'. The Observer. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^Foster, Anthony (24 November 2008). 'Bolt tops them againArchived 12 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine'. Jamaica Gleaner. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^Helps, Horace (16 August 2008). 'Bolt's gold down to yam power, father says'. Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ abcdefLayden, Tim (16 August 2008). 'The Phenom'. Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^Sinclair, Glenroy (15 August 2008). 'Bolts bonded'. Jamaica Gleaner. Archived from the original on 24 August 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ abLongmore, Andrew (24 August 2008). 'Brilliant Usain Bolt is on fast track to history'. The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^Frater, Adrian (5 August 2008). 'Bolt's Sherwood on 'gold alert''. Jamaica Gleaner. Archived from the original on 14 August 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ abcdeWilliams, Ollie (5 August 2008). 'Ten to watch: Usain Bolt'. BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ abcdLuton, Daraine (18 August 2008). 'Pablo McNeil – the man who put the charge in Bolt'. Jamaica Gleaner. Archived from the original on 26 August 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2008.

- ^Foster, Anthony (17 March 2009). 'Jarrett looking to produce some winners at Bolt's school'. Jamaica Star. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2012.